The Linux Boot Process

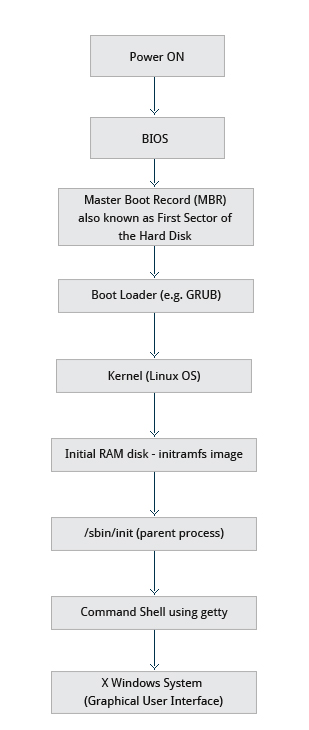

The Boot Process

Procedure for initializing the system.

BIOS

- When the computer is powered on, the Basic Input Output System (BIOS) initializes the hardware, including the screen and keyboard, and tests the main memory. This process is also called POST (Power On Self Test).

- The BIOS software is stored on a ROM chip on the motherboard. After this, the remainder of the boot process is controlled by the operating system (OS).

- Once the POST is completed, the system control passes from the BIOS to the boot loader.

Boot Loader

- The boot loader is usually stored on one of the hard disks in the system, either in the

- boot sector (for traditional BIOS/MBR systems) or

- the EFI partition (for more recent (Unified) Extensible Firmware Interface or EFI/UEFI systems).

- Up to this stage, the machine does not access any mass storage media. Thereafter, information on date, time, and the most important peripherals are loaded from the CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor) values (after a technology used for the battery-powered memory store which allows the system to keep track of the date and time even when it is powered off).

- A number of boot loaders exist for Linux; the most common ones are

- GRUB (for GRand Unified Boot loader),

- ISOLINUX (for booting from removable media), and

- DAS U-Boot (for booting on embedded devices/appliances).

- Most Linux boot loaders can present a user interface for choosing alternative options for booting Linux, and even other operating systems that might be installed. (Dual boot or Triple Boot)

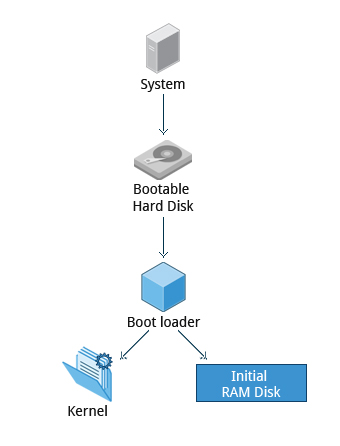

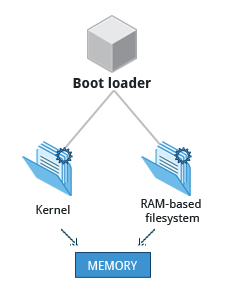

- When booting Linux, the boot loader is responsible for loading the kernel image and the initial RAM disk or file-system (which contains some critical files and device drivers needed to start the system) into memory.

Working of Boot Loader

The boot loader has two distinct stages:

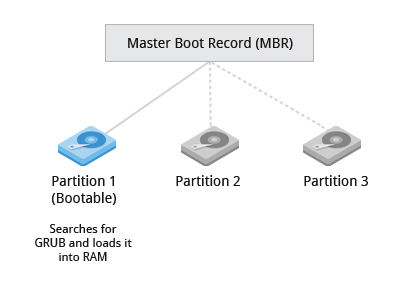

Stage 1

BIOS/MBR method: For systems using the BIOS/MBR method,

- The boot loader resides at the 1st sector of the hard disk, also known as the Master Boot Record (MBR).

- The size of the MBR is just 512 bytes. This 512-byte space is divided into three parts:

- Bootloader Code: The first 446 bytes.

- Partition Table: The next 64 bytes.

- Boot Signature: The final 2 bytes.

- In this stage, the boot loader examines the partition table and finds a bootable partition.

- Once it finds a bootable partition, it then searches for the second stage boot loader, for example GRUB, and loads it into RAM (Random Access Memory).

EFI/UEFI method: For systems using the EFI/UEFI method,

- UEFI firmware reads its Boot Manager data to determine which UEFI application is to be launched and from where (i.e. from which disk and partition the EFI partition can be found).

- The firmware then launches the UEFI application, for example GRUB, as defined in the boot entry in the firmware’s boot manager. This procedure is more complicated, but more versatile than the older MBR methods.

Stage 2

The second stage boot loader resides under /boot.

- A splash screen is displayed, which allows us to choose which operating system (OS) to boot.

- After choosing the OS, the boot loader loads the kernel of the selected operating system into RAM and passes control to it.

- Kernels are almost always compressed, so its first job is to un-compress itself.

- After this, it will check and analyze the system hardware and initialize any hardware device drivers built into the kernel.

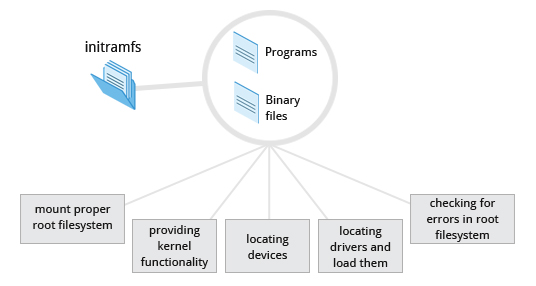

Initial RAM Disk

-

The initramfs (initial RAM–based file system) image contains programs and binary files that perform all actions needed to mount the proper root file-system, like providing kernel functionality for the needed file-system and device drivers for mass storage controllers with a facility called

udev(for user device), after the root file-system has been found, it is checked for errors and mounted.udevis responsible for figuring out which devices are present, locating the device drivers they need to operate properly, and loading them. -

The mount program instructs the operating system that a file-system is ready for use, and associates it with a particular point in the overall hierarchy of the file-system (the mount point). If this is successful, the

initramfsis cleared from RAM and the init program on the root file-system (/sbin/init) is executed.

init

inithandles the mounting and pivoting over to the final real root filesystem. If special hardware drivers are needed before the mass storage can be accessed, they must be in the initramfs image.

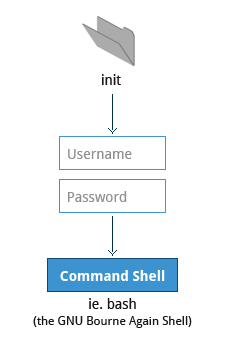

Text-Mode Login

- Near the end of the boot process, init starts a number of text-mode login prompts. These enable you to type your username, followed by your password, and to eventually get a command shell. Not visible if running Graphical Login Interface.

- The terminals which run the command shells can be accessed using the

ALT key + function key. - Most distributions start 6 text terminals and 1 graphics terminal starting with

F1orF2. - Within a graphical environment, switching to a text console requires pressing

CTRL-ALT + the appropriate function key (with F7 or F1 leading to the GUI). - Usually, the default command shell is bash (the GNU Bourne Again Shell), but there are a number of other advanced command shells available.

- The shell prints a text prompt, indicating it is ready to accept commands; after the user types the command and presses Enter, the command is executed, and another prompt is displayed after the command is done.

Kernel, init and Services

Linux Kernel

- The boot loader loads both the kernel and an initial RAM–based file system (initramfs) into memory, so it can be used directly by the kernel.

- When the kernel is loaded in RAM, it immediately initializes and configures the computer’s memory and also configures all the hardware attached to the system. This includes all processors, I/O subsystems, storage devices, etc. The kernel also loads some necessary user space applications.

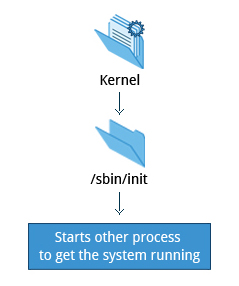

/sbin/init and Services

- Once the kernel has set up all its hardware and mounted the root file-system, the kernel runs

/sbin/init. This then becomes the initial process, which then starts other processes to get the system running. - The

/sbin/initprogram (usually just called init) is the first user-level process (or task) run on the system and continues to run until the system is shut down. - Most other processes on the system trace their origin ultimately to

init; exceptions include the so-called kernel processes. These are started by the kernel directly, and their job is to manage internal operating system details. - Besides starting the system,

initis responsible for keeping the system running and for shutting it down cleanly. One of its responsibilities is to act when necessary as a manager for all non-kernel processes; it cleans up after them upon completion, and restarts user login services as needed when users log in and out, and does the same for other background system services. - Traditionally, this process startup was done using conventions that date back to the 1980s and the System V variety of UNIX. This serial process had the system passing through a sequence of runlevels containing collections of scripts that start and stop services. Each runlevel supported a different mode of running the system. Within each runlevel, individual services could be set to run, or to be shut down if running.

- However, all major distributions have moved away from this sequential runlevel method of system initialization, although they usually emulate many System V utilities for compatibility purposes.

Startup Alternatives

- SysVinit

- viewed things as a serial process, divided into a series of sequential stages.

- Each stage required completion before the next could proceed.

- Thus, startup did not easily take advantage of the parallel processing that could be done on multiple processors or cores.

- Furthermore, shutdown and reboot was seen as a relatively rare event; exactly how long it took was not considered important.

- This is no longer true, especially with mobile devices and embedded Linux systems.

- Some modern methods, such as the use of containers , can require almost instantaneous startup times. Thus, systems now require methods with faster and enhanced capabilities.

Finally, the older methods required rather complicated startup scripts, which were difficult to keep universal across distribution versions, kernel versions, architectures, and types of systems. The two main alternatives developed were:

-

Upstart

- Developed by Ubuntu and first included in 2006

- Adopted in Fedora 9 (in 2008) and in RHEL 6 and its clones

-

systemd

- Adopted by Fedora first (in 2011)

- Adopted by RHEL 7 and SUSE

- Replaced Upstart in Ubuntu 16.04

- it has been adopted by almost all major distributions.

systemd

- Systems with systemd boots up faster than those with earlier init methods. This is largely because it replaces a serialized set of steps with aggressive parallelization techniques, which permits multiple services to be initiated simultaneously.

- Complicated startup shell scripts are replaced with simpler configuration files, which enumerate what has to be done before a service is started, how to execute service startup, and what conditions the service should indicate have been accomplished when startup is finished. One thing to note is that /sbin/init now just points to /lib/systemd/systemd; i.e. systemd takes over the init process.

The systemd system and session manager for Linux is now dominant in most major distributions. Features include the following:

- Boots faster than previous init systems

- Provides aggressive parallelization capabilities

- Uses socket and D-Bus activation for starting services

- Replaces shell scripts with programs

- Offers on-demand starting of daemons

- Keeps track of processes using

cgroups - Maintains mount and automount points

- Implements an elaborate transactional dependency-based service control logic

- Provides detailed start and stop functionality, including similar abilities to

cron

Instead of bash scripts, systemd uses .service files. Granular logging is provided by default using the name of the unit. Tracking and creating user processes without root privileges is another powerful ability of systemd.

systemd Configuration File Locations

systemd allows for multiple locations for its unit files, allowing for processes running under a non-root user, and inheritance from system unit files. Here are some typical locations (but may vary by distribution):

- System unit files:

/etc/systemd/systemand/lib/systemd/system - User unit files:

/etc/systemd/userand~/.config/systemd/user

On most systems,

/lib/systemd/is a symlink to/usr/lib/systemd/.

Here is an example of a standard system unit file from Debian:

/lib/systemd/system/dbus.service

[Unit]

Description=D-Bus System Message Bus

Documentation=man:dbus-daemon(1)

Requires=dbus.socket

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/bin/dbus-daemon --system --address=systemd: --nofork --nopidfile --systemd-activation ,

→ --syslog-only

ExecReload=/usr/bin/dbus-send --print-reply --system --type=method_call --dest=org.freedesktop.DBus / ,

→ org.freedesktop.DBus.ReloadConfig OOMScoreAdjust=-900SYSTEMD TOOLS

Tool to manage systemd services and units.

- Manage system state: start, stop, restart, reload services

- Enable/disable services at boot

- List and manage units (services, sockets, etc.)

- List and update targets (runlevels)

- Show status of services/units

- Edit service unit files

- Reload systemd manager configuration

Tool to query and view logs collected by systemd’s journal.

- View logs for all units, or specific units (

-u UNIT) - Filter logs by boot (

-b), time, priority, etc. - Search logs for keywords, errors, warnings

- View logs for specific time ranges

- Show logs in real-time (

-f) - Export logs to text file

- View logs for previous boots (

--list-boots)

systemctl

-

systemdcommand (systemctl) used for most basic tasks. -

Use of

systemctl-

Starting, stopping, restarting, & reloading a service on a currently running system:

sudo systemctl start|stop|restart|reload httpd.service -

Enabling or disabling a system service from starting up at system boot:

sudo systemctl enable|disable httpd.service -

To check the status of a service

sudo systemctl status httpd.service STATE Meaning Active Service Running Inactive Service Stopped Failed Crashed/Error/Timeout e.t.c -

In most cases, the

.servicecan be omitted. To make changes to service unit file:systemctl edit httpd.service --full -

After making changes to service unit file restarting the changes in service:

systemctl daemon-reload -

To show the status of everything that systemd controls:

systemctl -

To show all available services:

systemctl list-units -t service --all -

To show only active services:

systemctl list-units -t service -

To see the default run level

systemctl get-default -

To change the different target or change runlevel

systemctl set-default multi-user.target -

To list all units systemd has loaded

systemctl list-units --all

journalctl

-

-

Useful when troubleshooting with systemd units as it checks journal or log entries from all parts of the system.

-

By default, its logs may not be persistent across reboots. Persistence is typically enabled by creating the directory

/var/log/journal. -

Print all log entries from old to new

journalctl -

To see the logs from current boot

journalctl -b -

To see the log of a particular unit

journalctl -u UNIT

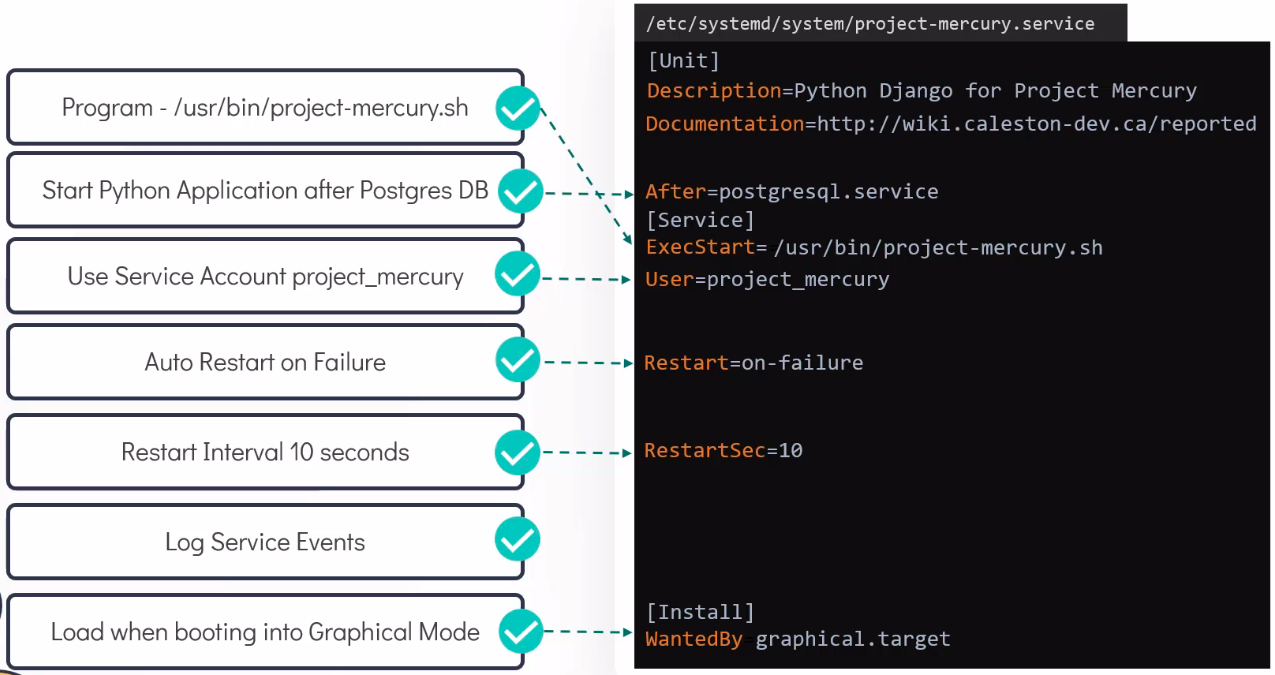

Creating service with requirements in systemd /etc/systemd/