Introduction

String Manipulation

The case Statement

Looping Constructs

Script Debugging

Some Additional Useful Techniques

Knowledge Check (Verified Certificate track only)

Summary

Introduction

- Manipulate strings to perform actions such as comparison and sorting.

- Use Boolean expressions when working with multiple data types, including strings or numbers, as well as files.

- Use case statements to handle command line options.

- Use looping constructs to execute one or more lines of code repetitively.

- Debug scripts using set x and set +x.

- Create temporary files and directories.

- Create and use random numbers.

String Manipulation

- A string variable contains a sequence of text characters. It can include letters, numbers, symbols and punctuation marks. Some examples include: abcde, 123, abcde 123, abcde-123, &acbde=%123.

- String operators include those that do comparison, sorting, and finding the length. The following table demonstrates the use of some basic string operators:

==Operator== ==Meaning== **[[ string1 > string2 ]]**Compares the sorting order of string1 and string2. **[[ string1 == string2 ]]**Compares the characters in string1 with the characters in string2. **myLen1=${\#string1}**Saves the length of string1 in the variable myLen1.

-

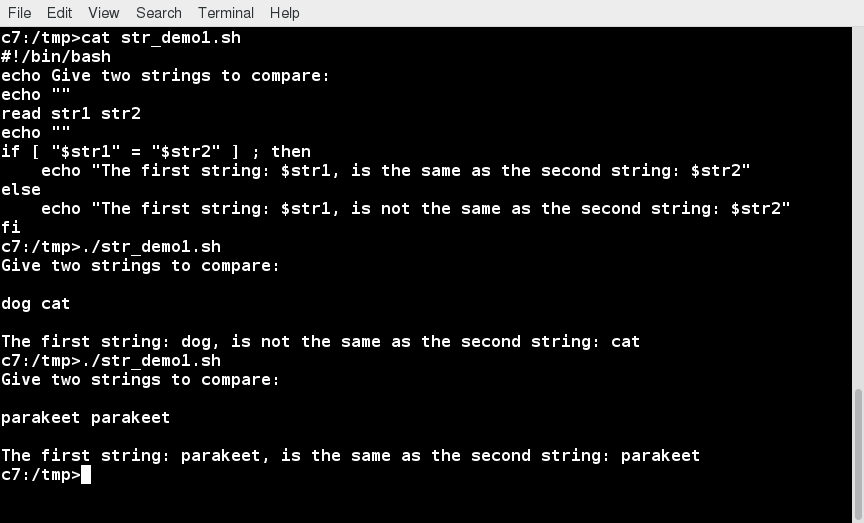

compare the first string with the second string and display an appropriate message using the if statement.

-

pass in a file name and see if that file exists in the current directory or not.

==Parts of a String==

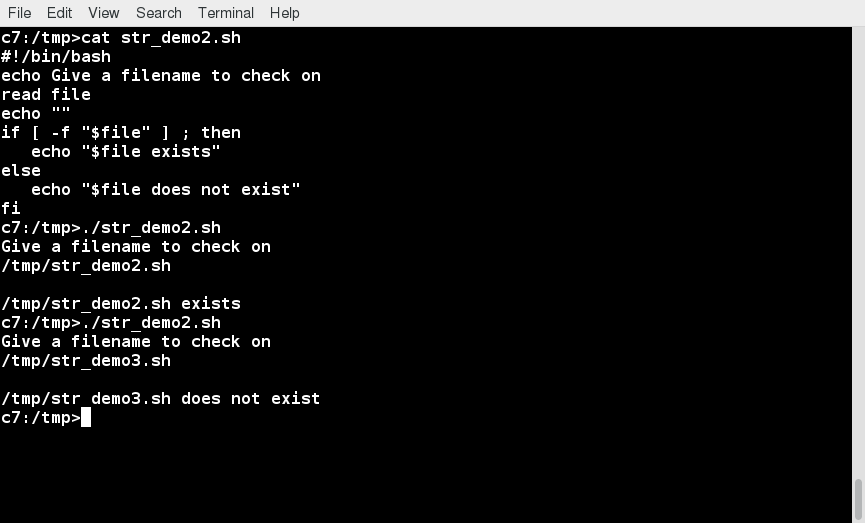

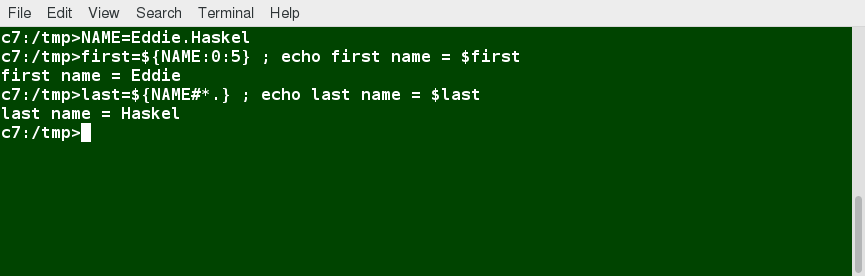

- At times, you may not need to compare or use an entire string.

- To extract the first n characters of a string we can specify:

**${string:0:n}**. Here, 0 is the offset in the string (i.e. which character to begin from) where the extraction needs to start and n is the number of characters to be extracted. - To extract all characters in a string after a dot (.), use the following expression:

**${string#*.}**.

-

Lab 16.1: String Tests and Operations

Write a script which reads two strings as arguments and then:

- Tests to see if the first string is of zero length, and if the other is of non-zero length, telling the user of both results.

- Determines the length of each string, and reports on which one is longer or if they are of equal length.

- Compares the strings to see if they are the same, and reports on the result.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named teststrings.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash # check two string arguments were given [[ $# -lt 2 ]] && \ echo "Usage: Give two strings as arguments" && exit 1 str1=$1 str2=$2 \#------------------------------------ ## test command echo "Is string 1 zero length? Value of 1 means FALSE" [ -z "$str1" ] echo $? # note if $str1 is empty, the test [ -z $str1 ] would fail # but [[ -z $str1 ]] succeeds # i.e., with [[ ]] it works even without the quotes echo "Is string 2 nonzero length? Value of 0 means TRUE;" [ -n $str2 ] echo $? ## comparing the lengths of two string len1=${\#str1} len2=${\#str2} echo length of string1 = $len1, length of string2 = $len2 if [ $len1 -gt $len2 ] then echo "String 1 is longer than string 2" else if [ $len2 -gt $len1 ] then echo "String 2 is longer than string 1" else echo "String 1 is the same length as string 2" fi fi ## compare the two strings to see if they are the same if [[ $str1 == $str2 ]] then echo "String 1 is the same as string 2" else if [[ $str1 != $str2 ]] then echo "String 1 is not the same as string 2" fi fi chmod +x teststrings.sh ./teststrings.sh str1 str2

The case Statement

The **case** statement is used in scenarios where the actual value of a variable can lead to different execution paths.

**case** statements are often used to handle command-line options.

Below are some of the advantages of using the case statement:

- It is easier to read and write.

- It is a good alternative to nested, multi-level if-then-else-fi code blocks.

- It enables you to compare a variable against several values at once.

- It reduces the complexity of a program.

![[/Untitled 80.png|Untitled 80.png]]

Structure of the case Statement

-

basic structure of the case statement:

case expression in pattern1) execute commands;; pattern2) execute commands;; pattern3) execute commands;; pattern4) execute commands;; * ) execute some default commands or nothing ;; esac![[/Untitled 1 44.png|Untitled 1 44.png]]

![[/Untitled 2 34.png|Untitled 2 34.png]]

-

Lab 16.2: Using the case Statement

Write a script that takes as an argument a month in numerical form (i.e. between 1 and 12), and translates this to the month name and displays the result on standard out (the terminal).

If no argument is given, or a bad number is given, the script should report the error and exit.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testcase.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash # Accept a number between 1 and 12 as # an argument to this script, then return the # the name of the month that corresponds to that number. # Check to see if the user passed a parameter. if [ $# -eq 0 ] then echo "Error. Give as an argument a number between 1 and 12." exit 1 fi # set month equal to argument passed for use in the script month=$1 ################################################ # The example of a case statement: case $month in 1) echo "January" ;; 2) echo "February" ;; 3) echo "March" ;; 4) echo "April" ;; 5) echo "May" ;; 6) echo "June" ;; 7) echo "July" ;; 8) echo "August" ;; 9) echo "September" ;; 10) echo "October" ;; 11) echo "November" ;; 12) echo "December" ;; *) echo "Error. No month matches: $month" echo "Please pass a number between 1 and 12." exit 2 ;; esac exit 0 Make it executable and run it: chmod +x teststrings.sh ./teststrings.sh 5

-

Looping Constructs

By using looping constructs, you can execute one or more lines of code repetitively, usually on a selection of values of data such as individual files. Usually, you do this until a conditional test returns either true or false, as is required.

Three types of loops are often used in most programming languages:

- for

- while

- until.

All these loops are easily used for repeating a set of statements until the exit condition is true.

![[/Untitled 3 22.png|Untitled 3 22.png]]

The for Loop

-

The for loop operates on each element of a list of items. The syntax for the for

loop is:for variable-name in list do execute one iteration for each item in the list until the list is finished done

Example of the for loop to print the sum of numbers 1 to 10:

![[/Untitled 4 18.png|Untitled 4 18.png]]

The while Loop

-

The while loop repeats a set of statements as long as the control command returns true. The syntax is:

while condition is true do Commands for execution ---- done -

The set of commands that need to be repeated should be enclosed between do and done.

-

You can use any command or operator as the condition. Often, it is enclosed within square brackets ([]).

-

Example of the while loop that calculates the factorial of a number

![[/Untitled 5 16.png|Untitled 5 16.png]]

The until Loop

-

The until loop repeats a set of statements as long as the control command is false. Thus, it is essentially the opposite of the while

loop. The syntax is:until condition is false do Commands for execution ---- doneSimilar to the while loop, the set of commands that need to be repeated should be enclosed between do

and

done. You can use any command or operator as the condition. -

Example of the until loop that computes factorials

![[/Untitled 6 14.png|Untitled 6 14.png]]

Script Debugging

Debugging bash Scripts

While working with scripts and commands, you may run into errors.

These may be due to an error in the script, such as an incorrect syntax, or other ingredients, such as a missing file or insufficient permission to do an operation.

These errors may be reported with a specific error code, but often just yield incorrect or confusing output.

how do you go about identifying and fixing an error? - Debugging helps you troubleshoot and resolve such errors, and is one of the most important tasks a system administrator performs.

Script Debug Mode

- Before fixing an error (or bug), it is vital to know its source.

- Run a bash script in debug mode either by doing

**bash –x ./script_file**, or bracketing parts of the script with**set -x**and**set +x**. - The debug mode helps identify the error because:

-

It traces and prefixes each command with the + character.

-

It displays each command before executing it.

-

It can debug only selected parts of a script (if desired) with:

set -x # turns on debugging ... set +x # turns off debugging

-

![[/Untitled 7 10.png|Untitled 7 10.png]]

Redirecting Errors to File and Screen

-

In UNIX/Linux, all programs that run are given three open file streams when they are started as listed in the table:

==File stream== ==Description== ==File Descriptor== **stdin**Standard Input, by default the keyboard/terminal for programs run from the command line 0 **stdout**Standard output, by default the screen for programs run from the command line 1 -

a shell script with a simple bug, which is then run and the error output is diverted to error.log. Using cat to display the contents of the error log adds in debugging.

![[/Untitled 8 9.png|Untitled 8 9.png]]

- Using redirection, we can save the stdout and stderr output streams to one file or two separate files for later analysis after a program or command is executed.

Some Additional Useful Techniques

Creating Temporary Files and Directories

- Temporary files (and directories) are meant to store data for a short time.

- Usually, one arranges it so that these files disappear when the program using them terminates.

- While you can also use

touchto create a temporary file, in some circumstances this may make it easy for hackers to gain access to your data. This is particularly true if the name and the file location of the temporary file are predictable. - The best practice is to create random and unpredictable filenames for temporary storage.

- One way to do this is with the

**mktemp**utility, as in the following examples. - The XXXXXXXX is replaced by

**mktemp**with random characters to ensure the name of the temporary file cannot be easily predicted and is only known within your program.==Command== ==Usage== **TEMP=$(mktemp /tmp/tempfile.XXXXXXXX)**To create a temporary file **TEMPDIR=$(mktemp -d /tmp/tempdir.XXXXXXXX)**To create a temporary directory

Example of Creating a Temporary File and Directory

-

Sloppiness in creation of temporary files can lead to real damage, either by accident or if there is a malicious actor. For example, if someone were to create a symbolic link from a known temporary file used by root to the /etc/passwd file, like this:

**$ ln -s /etc/passwd /tmp/tempfile**There could be a big problem if a script run by root has a line in like this:

**echo $VAR > /tmp/tempfile**The password file will be overwritten by the temporary file contents.

-

To prevent such a situation, make sure you randomize your temporary file names by replacing the above line with the following lines:

**TEMP=$(mktemp /tmp/tempfile.XXXXXXXX)echo $VAR > $TEMP**

Discarding Output with **/dev/null**

-

Certain commands (like

**find**) will produce voluminous amounts of output, which can overwhelm the console. To avoid this, we can redirect the large output to a special file (a device node) called**/dev/null**. This pseudofile is also called the bit bucket or black hole. -

All data written to it is discarded and write operations never return a failure condition. Using the proper redirection operators, it can make the output disappear from commands that would normally generate output to

**stdout**and/or**stderr**:**$ ls -lR /tmp > /dev/null** -

In the above command, the entire standard output stream is ignored, but any errors will still appear on the console. However, if one does:

**$ ls -lR /tmp >& /dev/null**both

**stdout**and**stderr**will be dumped into**/dev/null**.

Random Numbers and Data

- It is often useful to generate random numbers and other random data when performing tasks such as:

- Performing security-related tasks

- Reinitializing storage devices

- Erasing and/or obscuring existing data

- Generating meaningless data to be used for tests.

- Such random numbers can be generated by using the

**$RANDOM**environment variable, which is derived from the Linux kernel’s built-in random number generator, or by the OpenSSL library function, which uses the FIPS140 (Federal Information Processing Standard) algorithm to generate random numbers for encryption

How the Kernel Generates Random Numbers

-

Some servers have hardware random number generators that take as input different types of noise signals, such as thermal noise and photoelectric effect. A transducer converts this noise into an electric signal, which is again converted into a digital number by an A-D converter. This number is considered random. However, most common computers do not contain such specialized hardware and, instead, rely on events created during booting to create the raw data needed.

-

Regardless of which of these two sources is used, the system maintains a so-called entropy pool of these digital numbers/random bits. Random numbers are created from this entropy pool.

-

The Linux kernel offers the

**/dev/random**and**/dev/urandom**device nodes, which draw on the entropy pool to provide random numbers which are drawn from the estimated number of bits of noise in the entropy pool. -

**/dev/random**is used where very high quality randomness is required, such as one-time pad or key generation, but it is relatively slow to provide values. -

**/dev/urandom**is faster and suitable (good enough) for most cryptographic purposes. -

Furthermore, when the entropy pool is empty,

**/dev/random**is blocked and does not generate any number until additional environmental noise (network traffic, mouse movement, etc.) is gathered, whereas**/dev/urandom**reuses the internal pool to produce more pseudo-random bits. -

Lab 16.3: Using Random Numbers

Write a script which:

- Takes a word as an argument.

- Appends a random number to it.

- Displays the answer.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testcase.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash ## # check to see if the user supplied in the parameter. [[ $# -eq 0 ]] && echo "Usage: $0 word" && exit 1 echo "$1-$RANDOM" exit 0 Make it executable and run it: chmod +x testrandom.sh ./testrandom.sh strA

Knowledge Check (Verified Certificate track only)

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-27-29.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-31-31.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-32-50.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-34-10.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-29-15.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-32-03.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-33-35.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-34-32.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-05_07-35-03.png]]

Summary

- You can manipulate strings to perform actions such as comparison, sorting, and finding length.

- You can use Boolean expressions when working with multiple data types, including strings or numbers, as well as files.

- The output of a Boolean expression is either true or false.

- Operators used in Boolean expressions include the && (AND), || (OR), and ! (NOT) operators.

- We looked at the advantages of using the case statement in scenarios where the value of a variable can lead to different execution paths.

- Script debugging methods help troubleshoot and resolve errors.

- The standard and error outputs from a script or shell commands can easily be redirected into the same file or separate files to aid in debugging and saving results.

- Linux allows you to create temporary files and directories, which store data for a short duration, both saving space and increasing security.

- Linux provides several different ways of generating random numbers, which are widely used.