Introduction

Features and Capabilities

Syntax

Constructs

Knowledge Check (Verified Certificate track only)

Summary

Introduction

- Explain the features and capabilities of bash shell scripting.

- Know the basic syntax of scripting statements.

- Be familiar with various methods and constructs used.

- Test for properties and existence of files and other objects.

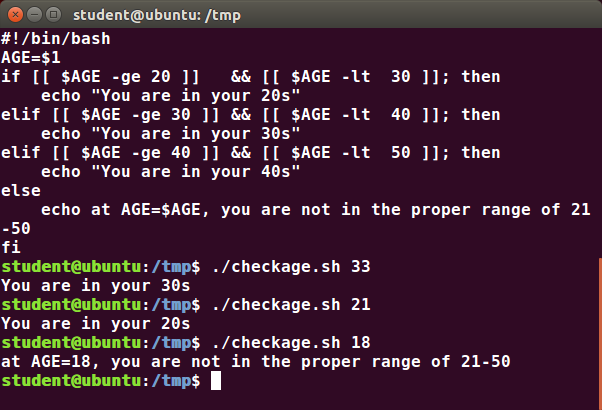

- Use conditional statements, such as if-then-else blocks.

- Perform arithmetic operations using scripting language.

Features and Capabilities

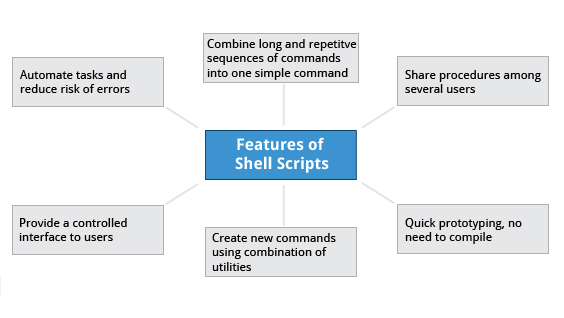

==Why Scripting?==

- Automate Daily backup

- Automate installation and Patching of software on multiple servers

- Monitor System periodically

- Raise alarms and send notifications

- Troubleshooting and Audits

- Many more

==Shell Scripting==

- Suppose you want to look up a filename, check if the associated file exists, and then respond accordingly, displaying a message confirming or not confirming the file’s existence.

- If you only need to do it once, you can just type a sequence of commands at a terminal. However, if you need to do this multiple times, automation is the way to go.

- In order to automate sets of commands, you will need to learn how to write shell scripts.

- Most commonly in Linux, these scripts are developed to be run under the bash command shell interpreter.

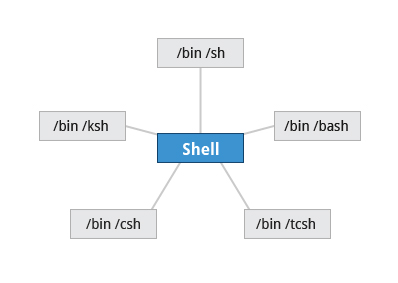

==Command Shell Choices==

- The command interpreter is tasked with executing statements that follow it in the script. Commonly used interpreters include:

**/usr/bin/perl**,**/bin/bash**,**/bin/csh**,**/usr/bin/python**and**/bin/sh**. - Typing a long sequence of commands at a terminal window can be complicated, time consuming, and error prone.

- By deploying shell scripts, using the command line becomes an efficient and quick way to launch complex sequences of steps.

- The fact that shell scripts are saved in a file also makes it easy to use them to create new script variations and share standard procedures with several users.

- Linux provides a wide choice of shells; exactly what is available on the system is listed in

**/etc/shells**.

==A Simple bash Script==

-

Let’s write a simple bash script that displays a one line message on the screen. Either type:

**$ cat > hello.sh****#!/bin/bash

echo “Hello Linux Foundation Student”

**and press ENTER and CTRL-D to save the file, or just create hello.sh in your favorite text editor.

-

Then, type

**chmod +x hello.sh**to make the file executable by all users. -

You can then run the script by typing

**./hello.sh**or by doing:**$ bash hello.sh**Hello Linux Foundation Student

==Interactive Example Using bash Scripts==

- Now, let’s see how to create a more interactive example using a bash script. The user will be prompted to enter a value, which is then displayed on the screen. The value is stored in a temporary variable, name.

- We can reference the value of a shell variable by using a

**$**in front of the variable name, such as**$name**. - To create this script, you need to create a file named

**getname.sh**in your favorite editor with the following content:

#!/bin/bash

# Interactive reading of a variable

echo "ENTER YOUR NAME"

read name

# Display variable input

echo "The name given was :$name"- Once again, make it executable by doing

**chmod +x getname.sh**.

Important

NOTE: The hash-tag/pound-sign/number-sign (#) is used to start comments in the script and can be placed anywhere in the line (the rest of the line is considered a comment). However, note the special magic combination of #!, used on the first line, is a unique exception to this rule.

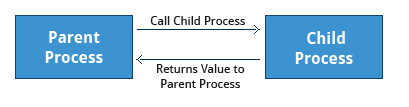

==Return Values==

- All shell scripts generate a return value upon finishing execution, which can be explicitly set with the exit statement.

- Return values permit a process to monitor the exit state of another process, often in a parent-child relationship.

- Knowing how the process terminates enables taking any appropriate steps which are necessary or contingent on success or failure.

==Viewing Return Values==

-

As a script executes, one can check for a specific value or condition and return success or failure as the result.

-

By convention, success is returned as

**0**, and failure is returned as a non-zero value. -

An easy way to demonstrate success and failure completion is to execute ls on a file that exists as well as one that does not, the return value is stored in the environment variable represented by

**$?**:**$ ls /etc/logrotate.conf****

/etc/logrotate.conf

****$ echo $?****

0

**- In this example, the system is able to locate the file /etc/logrotate.conf and ls returns a value of 0 to indicate success.

- When run on a non-existing file, it returns 2.

Syntax

==Basic Syntax and Special Characters==

- Scripts require you to follow a standard language syntax. Rules delineate how to define variables and how to construct and format allowed statements, etc.

==Character== ==Description== **#**Used to add a comment, except when used as #, or as #! when starting a script **\**Used at the end of a line to indicate continuation on to the next line **;**Used to interpret what follows as a new command to be executed next **$**Indicates what follows is an environment variable **>**Redirect output **>>**Append output **<**Redirect input **|**Used to pipe the result into the next command

==Splitting Long Commands Over Multiple Lines==

-

Sometimes, commands are too long to either easily type on one line, or to grasp and understand (even though there is no real practical limit to the length of a command line).

-

In this case, the concatenation operator (

\), the backslash character, is used to continue long commands over several lines.-

Here is an example of a command installing a long list of packages on a system using Debian package management:

$~/> cd $HOME $~/> sudo apt-get install autoconf automake bison build-essential \ chrpath curl diffstat emacs flex gcc-multilib g++-multilib \ libsdl1.2-dev libtool lzop make mc patch \ screen socat sudo tar texinfo tofrodos u-boot-tools unzip \ vim wget xterm zip

-

-

The command is divided into multiple lines to make it look readable and easier to understand.

-

The ** operator at the end of each line causes the shell to combine (concatenate) multiple lines and executes them as one single command.

==Putting Multiple Commands on a Single Line==

-

Users sometimes need to combine several commands and statements and even conditionally execute them based on the behavior of operators used in between them. This method is called chaining of commands.

-

There are several different ways to do this, depending on what you want to do. The

;(semicolon) character is used to separate these commands and execute them sequentially, as if they had been typed on separate lines. Each ensuing command is executed whether or not the preceding one succeeded. -

Thus, the three commands in the following example will all execute, even if the ones preceding them fail:

**$ make ; make install ; make clean** -

However, you may want to abort subsequent commands when an earlier one fails. You can do this using the

**&&**(and) operator as in:**$ make && make install && make clean**If the first command fails, the second one will never be executed.

-

A final refinement is to use the

**||**(or) operator, as in:**$ cat file1 || cat file2 || cat file3**In this case, you proceed until something succeeds and then you stop executing any further steps.

-

Chaining commands is not the same as piping them; in the later case succeeding commands begin operating on data streams produced by earlier ones before they complete, while in chaining each step exits before the next one starts.

==Output Redirection==

-

Most operating systems accept input from the keyboard and display the output on the terminal. However, in shell scripting you can send the output to a file. The process of diverting the output to a file is called output redirection.

-

The > character is used to write output to a file.

-

For example, the following command sends the output of free to /tmp/free.out:

**$ free > /tmp/free.out** -

To check the contents of /tmp/free.out, at the command prompt type

**cat /tmp/free.out** -

Two > characters (

**>>**``)will append output to a file if it exists, and act just like > if the file does not already exist.

==Input Redirection==

-

The input of a command can be read from a file. The process of reading input from a file is called input redirection and uses the

**<**character. -

The following three commands (using

**wc**to count the number of lines, words and characters in a file) are entirely equivalent and involve input redirection, and a command operating on the contents of a file:**$ wc < /etc/passwd**49 105 2678 /etc/passwd**$ wc /etc/passwd**49 105 2678 /etcpasswd**$ cat /etc/passwd | wc**49 105 2678

==Built-In Shell Commands==

- Shell scripts execute sequences of commands and other types of statements. These commands can be:

- Compiled applications

- Built-in bash commands

- Shell scripts or scripts from other interpreted languages, such as perl and Python.

- Compiled applications are binary executable files, generally residing on the filesystem in well-known directories such as

**/usr/bin**. - Shell scripts always have access to applications such as

**rm**,**ls**,**df**,**vi**, and**gzip**, which are programs compiled from lower level programming languages such as C. - In addition, bash has many built-in commands, which can only be used to display the output within a terminal shell or shell script.

- Sometimes, these commands have the same name as executable programs on the system, such as

**echo**, which can lead to subtle problems. - bash built-in commands include

**cd**,**pwd**,**echo**,**read**,**logout**,**printf**,**let**, and**ulimit**. Thus, slightly different behavior can be expected from the built-in version of a command such as echo as compared to /bin/echo.

![[/Untitled 79.png|Untitled 79.png]]

==Script Parameters==

-

Users often need to pass parameter values to a script, such as a filename, date, etc. Scripts will take different paths or arrive at different values according to the parameters (command arguments) that are passed to them. These values can be text or numbers as in:

**$ ./script.sh /tmp****$ ./script.sh 100 200** -

Within a script, the parameter or an argument is represented with a $ and a number or special character. The table lists some of these parameters.

| ==Parameter== | ==Meaning== |

**$0** |

Script name |

**$1** |

First parameter |

**$2, $3, etc.** |

Second, third parameter, etc. |

**$*** |

All parameters |

**$#** |

Number of arguments |

==Command Substitution==

-

At times, you may need to substitute the result of a command as a portion of another command. It can be done in two ways:

- By enclosing the inner command in

**$( )** - By enclosing the inner command with backticks

**(`)**

- By enclosing the inner command in

-

The second, backticks form, is deprecated in new scripts and commands. No matter which method is used, the specified command will be executed in a newly launched shell environment, and the standard output of the shell will be inserted where the command substitution is done.

-

Virtually any command can be executed this way. While both of these methods enable command substitution, the

**$( )**method allows command nesting. New scripts should always use this more modern method. For example:**$ ls /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/** -

In the above example, the output of the command

**uname –r**(which will be something like 5.13.3), is inserted into the argument for the**ls**command.

==Environment Variables==

- Most scripts use variables containing a value, which can be used anywhere in the script.

- These variables can either be user or system-defined.

- Many applications use such environment variables for supplying inputs, validation, and controlling behavior.

==Exporting Environment Variables==

-

By default, the variables created within a script are available only to the subsequent steps of that script.

-

Any child processes (sub-shells) do not have automatic access to the values of these variables.

-

To make them available to child processes, they must be promoted to environment variables using the export statement, as in:

**export VAR=value**or

**VAR=value ; export VAR** -

While child processes are allowed to modify the value of exported variables, the parent will not see any changes; exported variables are not shared, they are only copied and inherited.

-

Typing

**export**with no arguments will give a list of all currently exported environment variables.

==Functions==

-

A function is a code block that implements a set of operations.

-

Functions are useful for executing procedures multiple times, perhaps with varying input variables. Functions are also often called subroutines. Using functions in scripts requires two steps:

- Declaring a function

- Calling a function

-

The function declaration requires a name which is used to invoke it. The proper syntax is:

**function_name () { command...}** -

For example, the following function is named display:

**display () { echo "This is a sample function"}** -

The function can be as long as desired and have many statements.

-

Once defined, the function can be called later as many times as necessary.

-

Lab 15.2: Working with Files and Directories in a Script

Write a script which:

- Prompts the user for a directory name and then creates it with

**mkdir**. - Changes to the new directory and prints out where it is using

**pwd**. - Using

**touch**, creates several empty files and runs ls on them to verify they are empty. - Puts some content in them using

**echo**and redirection. - Displays their content using

**cat**. - Says goodbye to the user and cleans up after itself.

-

==Solution==

#!/bin/bash # Prompts the user for a directory name and then creates it with mkdir. echo "Give a directory name to create:" read NEW_DIR # Save original directory so we can return to it (could also just use pushd, popd) ORIG_DIR=$(pwd) # check to make sure it doesn't already exist! [[ -d $NEW_DIR ]] && echo $NEW_DIR already exists, aborting && exit mkdir $NEW_DIR # Changes to the new directory and prints out where it is using pwd. cd $NEW_DIR pwd # Using touch, creates several empty files and runs ls on them to verify they are empty. for n in 1 2 3 4 do touch file$n done ls file? # (Could have just done touch file1 file2 file3 file4, just want to show do loop!) # Puts some content in them using echo and redirection. for names in file? do echo This file is named $names > $names done # Displays their content using cat cat file? # Says goodbye to the user and cleans up after itself cd $ORIG_DIR rm -rf $NEW_DIR echo "Goodbye My Friend!"

- Prompts the user for a directory name and then creates it with

-

Lab 15.3: Passing Arguments

Write a script that takes exactly one argument, and prints it back out to standard output. Make sure the script generates a usage message if it is run without giving an argument.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testarg.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash # # check for an argument, print a usage message if not supplied. # if [ $# -eq 0 ] ; then echo "Usage: $0 argument" exit 1 fi echo $1 exit 0 Make it executable and run it: chmod +x testarg.sh ./testarg.sh Hello

-

-

Lab 15.4: Environment Variables

Write a script which:

- Asks the user for a number, which should be “1” or “2”. Any other input should lead to an error report.

- Sets an environmental variable to be “Yes” if it is “1”, and “No” if it is “2”.

- Exports the environmental variable and displays it.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testenv.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash echo "Enter 1 or 2, to set the environmental variable EVAR to Yes or No" read ans # Set up a return code RC=0 if [ $ans -eq 1 ] then export EVAR="Yes" else if [ $ans -eq 2 ] then export EVAR="No" else # can only reach here with a bad answer export EVAR="Unknown" RC=1 fi fi echo "The value of EVAR is: $EVAR" exit $RC Make it executable and run it: chmod +x testenv.sh ./testenv.sh

-

Lab 15.5: Working with Functions

Write a script which:

- Asks the user for a number (1, 2 or 3).

- Calls a function with that number in its name. The function should display a message with its name included.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testfun.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash # Functions (must be defined before use) func1() { echo " This message is from function 1" } func2() { echo " This message is from function 2" } func3() { echo " This message is from function 3" } # Beginning of the main script # prompt the user to get their choice echo "Enter a number from 1 to 3" read n # Call the chosen function func$n Make it executable and run it: student:/tmp> chmod +x testfun.sh student:/tmp> ./testfun.sh

Constructs

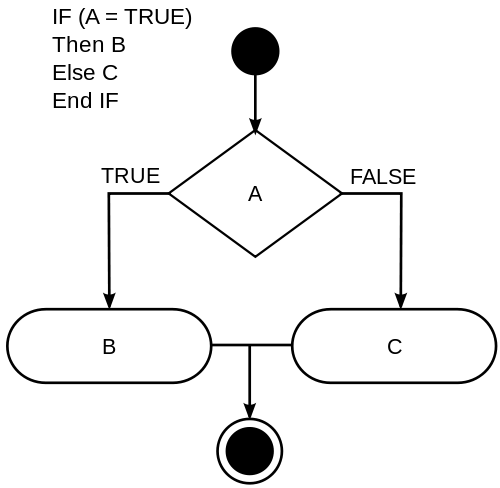

==The if Statement==

-

Conditional decision making, using an if statement, is a basic construct that any useful programming or scripting language must have.

-

When an if statement is used, the ensuing actions depend on the evaluation of specified conditions, such as:

- Numerical or string comparisons

- Return value of a command (0 for success)

- File existence or permissions.

-

In compact form, the syntax of an if statement is:

**if TEST-COMMANDS; then CONSEQUENT-COMMANDS; fi** -

A more general definition is:

if condition then statements else statements fi

==Using the if Statement==

-

In the following example, an if statement checks to see if a certain file exists, and if the file is found, it displays a message indicating success or failure:

if [ -f "$1" ] then echo file "$1 exists" else echo file "$1" does not exist fi -

We really should also check first that there is an argument passed to the script (

**$1**) and abort if not. -

Notice the use of the square brackets (

**[]**) to delineate the test condition. -

In modern scripts, you may see doubled brackets as in

**[[ -f /etc/passwd ]]**. -

This is not an error. It is never wrong to do so and it avoids some subtle problems, such as referring to an empty environment variable without surrounding it in double quotes.

==The elif Statement==

if [ sometest ] ; then

echo Passed test1

elif [ somothertest ] ; then

echo Passed test2

fi==Testing for Files==

-

bash provides a set of file conditionals, that can be used with the if statement, including those in the table.

-

You can use the

**if**statement to test for file attributes, such as:- File or directory existence

- Read or write permission

- Executable permission.

-

For example, in the following example:

if [ -x /etc/passwd ] ; then ACTION fithe if statement checks if the file /etc/passwd is executable, which it is not. Note the very common practice of putting:

**; then**on the same line as the

**if**statement. -

You can view the full list of file conditions typing:

**man 1 test**

| ==Condition== | ==Meaning== |

| -e file | Checks if the file exists. |

| -d file | Checks if the file is a directory. |

| -f file | Checks if the file is a regular file (i.e. not a symbolic link, device node, directory, etc.) |

| -s file | Checks if the file is of non-zero size. |

| -g file | Checks if the file has sgid set. |

| -u file | Checks if the file has suid set. |

| -r file | Checks if the file is readable. |

| -w file | Checks if the file is writable. |

| -x file | Checks if the file is executable. |

==Boolean Expressions==

- Boolean expressions evaluate to either TRUE or FALSE, and results are obtained using the various Boolean operators

- If you have multiple conditions strung together with the

**&&**operator, processing stops as soon as a condition evaluates to false.- For example, if you have

**A && B && C**and A is true but B is false, C will never be executed.

- For example, if you have

- Likewise, if you are using the

**||**operator, processing stops as soon as anything is true.- For example, if you have

**A || B || C**and A is false and B is true, you will also never execute C.

- For example, if you have

==Example of Testing of Strings==

-

You can use the

**if**statement to compare strings using the operator == (two equal signs). The syntax is as follows:**if [ string1 == string2 ] ; then ACTIONfi** -

Note that using one

**=**sign will also work, but some consider it deprecated usage.

| Operator | Operation | Meaning |

**&&** |

AND | The action will be performed only if both the conditions evaluate to true. |

**|** |

OR | The action will be performed if any one of the conditions evaluate to true. |

==Numerical Tests==

-

The syntax for comparing numbers is as follows:

**exp1 -op exp2**

| ==Operator== | ==Meaning== |

**-eq** |

Equal to |

**-ne** |

Not equal to |

**-gt** |

Greater than |

**-lt** |

Less than |

**-ge** |

Greater than or equal to |

**-le** |

Less than or equal to |

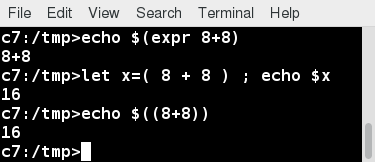

==Arithmetic Expressions==

-

Arithmetic expressions can be evaluated in the following three ways (spaces are important!):

-

Using the

**expr**utility**expr**is a standard but somewhat deprecated program. The syntax is as follows:**expr 8 + 8echo $(expr 8 + 8)** -

Using the

**$((...))**syntax

This is the built-in shell format. The syntax is as follows:**echo $((x+1))**

-

-

Using the built-in shell command

**let**.

The syntax is as follows:**let x=( 1 + 2 ); echo $x**

In modern shell scripts, the use of **expr** is better replaced with **var=$((...))**

-

Lab 15.6: Arithmetic and Functions

Write a script that will act as a simple calculator for add, subtract, multiply and divide.

- Each operation should have its own function.

- Any of the three methods for bash arithmetic, ($((..)), let, or expr) may be used.

- The user should give 3 arguments when executing the script:The first should be one of the letters a, s, m, or d to specify which math operation.The second and third arguments should be the numbers that are being operated on.

- The script should detect for bad or missing input values and display the results when done.

-

==Solution==

Create a file named testmath.sh, with the content below.

#!/bin/bash # Functions. must be before the main part of the script # in each case method 1 uses $((..)) # method 2 uses let # method 3 uses expr add() { answer1=$(($1 + $2)) let answer2=($1 + $2) answer3=`expr $1 + $2` } sub() { answer1=$(($1 - $2)) let answer2=($1 - $2) answer3=`expr $1 - $2` } mult() { answer1=$(($1 * $2)) let answer2=($1 * $2) answer3=`expr $1 \* $2` } div() { answer1=$(($1 / $2)) let answer2=($1 / $2) answer3=`expr $1 / $2` } # End of functions # # Main part of the script # need 3 arguments, and parse to make sure they are valid types op=$1 ; arg1=$2 ; arg2=$3 [[ $# -lt 3 ]] && \ echo "Usage: Provide an operation (a,s,m,d) and two numbers" && exit 1 [[ $op != a ]] && [[ $op != s ]] && [[ $op != d ]] && [[ $op != m ]] && \ echo operator must be a, s, m, or d, not $op as supplied # ok, do the work! if [[ $op == a ]] ; then add $arg1 $arg2 elif [[ $op == s ]] ; then sub $arg1 $arg2 elif [[ $op == m ]] ; then mult $arg1 $arg2 elif [[ $op == d ]] ; then div $arg1 $arg2 else echo $op is not a, s, m, or d, aborting ; exit 2 fi # Show the answers echo $arg1 $op $arg2 : echo 'Method 1, $((..)),' Answer is $answer1 echo 'Method 2, let, ' Answer is $answer2 echo 'Method 3, expr, ' Answer is $answer3 Make it executable and run it: student:/tmp> chmod +x testmath.sh student:/tmp> ./testmath.sh

Knowledge Check (Verified Certificate track only)

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-08-50.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-09-30.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-10-01.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-08-14.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-07-38.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-12-46.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-10-42.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-11-27.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-12-12.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-06-29.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-07-11.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-13-09.png]]

![[Screenshot_from_2022-07-03_20-13-41.png]]

Summary

- Scripts are a sequence of statements and commands stored in a file that can be executed by a shell. The most commonly used shell in Linux is bash.

- Command substitution allows you to substitute the result of a command as a portion of another command.

- Functions or routines are a group of commands that are used for execution.

- Environmental variables are quantities either preassigned by the shell or defined and modified by the user.

- To make environment variables visible to child processes, they need to be exported**.**

- Scripts can behave differently based on the parameters (values) passed to them.

- The process of writing the output to a file is called output redirection.

- The process of reading input from a file is called input redirection.

- The if statement is used to select an action based on a condition.

- Arithmetic expressions consist of numbers and arithmetic operators, such as +, , and .